The Mandela Effect: Part One

I am a fourth generation South African with Indian roots. During the 1800s, when South Africa and India were both colonized by the British, my ancestors were brought to South Africa as indentured laborers to work the railroads, coal mines and sugar cane fields. They left India for various reasons, among them being the current state of government in India, family issues, or just an adventure.

I am a fourth generation South African with Indian roots. During the 1800s, when South Africa and India were both colonized by the British, my ancestors were brought to South Africa as indentured laborers to work the railroads, coal mines and sugar cane fields. They left India for various reasons, among them being the current state of government in India, family issues, or just an adventure.

By the time their contract ended, most of the Indians working in South Africa had established a community—building schools, places of worship and starting informal businesses. My ancestors, like many other Indians, decided to stay and eventually this caused many to lose contact with our relatives back in India.

The Group Areas Act was enacted in 1950 and the circumstances of Apartheid outlined four distinct races. The “whites” of European descent; the “Indians”, like myself, who were called “Asians”; the “Africans”, who are the natives of South Africa; and the “Colored”, who emerged from the intermarriage of the whites and the Africans. This emphasized and enforced the actionable meaning behind Apartheid, “heid” meaning to live apart. Apartheid made it illegal for these four racial groups to live within the same residential areas.

Due to these racial barriers, I grew up in what was called “Little India”, simply due to the fact that everyone I lived around was Indian. I went to school with Indians, I socialized with Indians, and many of my informal interactions were with Indians. When venturing into the main city, interactions with other races became very rare. On the occasions that you did visit a park, movie theater, or any public place you would see “whites only” signs on benches. As someone of another race, you could be fined for using the facilities that were used by white citizens. In terms of segregation and mentalities, it seemed to be very much like the United States’ Civil Rights movement.

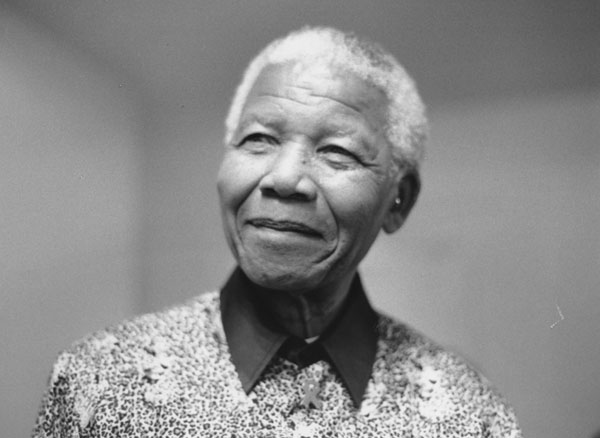

The Rise of Mandela: 1990s

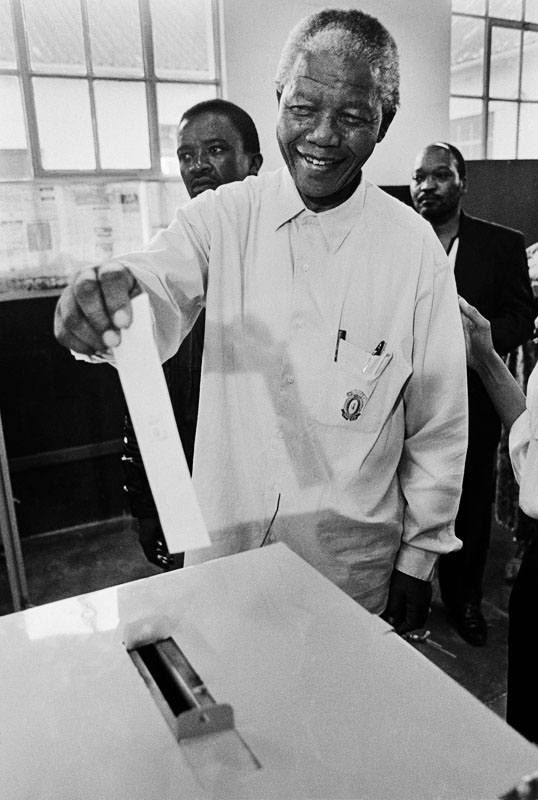

In 1990, Nelson Mandela was released from prison, mainly due to the immense pressure that was being put on the South Africa’s government from outside governments and parties. There were talks of international sanctions and nations refusing to work with South Africa if Mandela was not released. The mentalities of white South Africans during Apartheid were not ideal. They believed the four races to be unequal and it was exemplified in their words and actions. Such as, whites were only allowed to vote during the apartheid era. However, in 1994, when Nelson Mandela ran for president, everyone over the age of 18 was allowed vote regardless of race, and many took advantage of this newfound opportunity.

I have many memories from that day. I recall the polling stations opening at 6 a.m. but my family, being so excited, didn’t sleep a wink the night before. As a family, we were up by 4 a.m. and heading out the door. Yet, by the time we arrived at the polling stations there were already lines down the street with voters. Such waves of excitement swept over the crowds that no one minded the many hours they had been standing in line.

In South Africa, you don’t vote for an individual, you vote for a party. So I remember looking at the long ballot in front of me, wondering if I’d put my Xs in the right places—you get nervous about that sort of thing when you’re so excited and it is easy to make mistakes, so I just hoped I’d put my X next to the ANC (African National Congress, the party of Nelson Mandela) and not next to the National Party.

Once my peers and I finished voting, we got into cars and transported others to the voting stations. We did this all day and, by the end of the day, we were exhausted. Yet, this didn’t keep us from staying up and waiting for the results to come in. By 10 p.m., the ANC was winning by a huge margin and we knew Nelson Mandela was going to be our next president but we waited until midnight to pop the champagne.

As a child growing up in South Africa, I never quite felt that I belonged there. I felt that cultural norms that did not align with my own were being pushed upon me. When singing the national anthem or learning Afrikaans, I would do so begrudgingly just because I didn’t feel like it belonged to me. So, it was not until I actually had the opportunity to vote that I felt like I belonged in the country that I resided in. I finally felt as if I had a country.

By Ansuyah Naiken, Global Competency Training Manager

To read the second half of Ansuyah’s story, including her chance encounter with Nelson Mandela and her thoughts on Mandela’s legacy, visit The International Center’s blog on Tuesday, July 18, the date that would have been Mandela’s 99th birthday. You can also follow us on Facebook and Twitter for updates.